Greetings, Looking Glass Travellers!

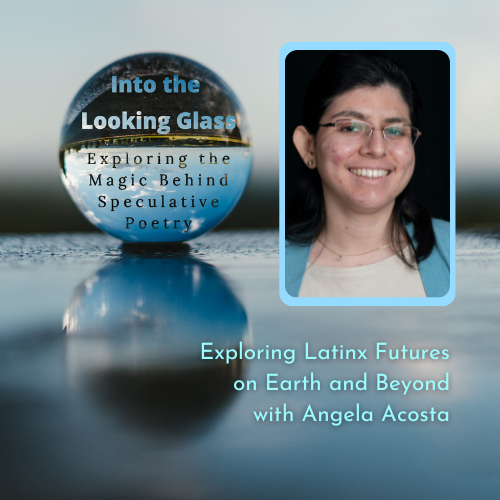

For episode four of our second season, Brittany is back at the mic for a fun chat with bilingual poet, author, lecturer, and translator Angela Acosta.

Scroll down for Angela’s bio, a list of links mentioned, the writing prompt of the month, and a transcript of this episode.

Angela Acosta is a Latina poet, translator, and researcher of Spanish literature who grew up in the state of Florida. She’s earned several degrees in Anglophone and Hispanophone literary fields, including, most recently, a PhD in Iberian Studies from Ohio State University.

Her latest academic investigations, teaching, and creative writing endeavors all aim to shine new light on the work of early 20th-century Spanish women authors.

Verse translations and articles by Angela have appeared in Metamorphoses, Ámbitos Feministas, Feminist Modernist Studies, and elsewhere, and you can read her original poetry in both Spanish and English in Space and Time, Radon Journal, Apparition Lit, and numerous other publications online and in print, including in her 2022 collection Summoning Space Travelers and her 2023 chapbook Fourth Generation Chicana Unicorn.

You can follow Angela’s work on her author website, where she regularly posts poetry and fiction publication updates. You can learn more about her past and current academic activities at her Davidson College page, and you can also keep an eye on her Instagram for news.

works by Angela

- Summoning Space Travelers (poetry collection, Hiraeth Publishing)

- Fourth Generation Chicana Unicorn (chapbook, dancing girl press)

- “Paradise of the Abyss,” Mithila Review Aug. 2022

- “May We Be Named,” Somos en escrito Jan. 2023

- “T & R Used Books & Curios,” Utopia June/July 2023

- “Tamales on Mars,” The Sprawl Mag 1.1

- “Cripping Outer Space,” Wordgathering 3

- “Gift of the Ancestors,” The Sprawl Mag 1.1

- “Oración para los antiguos viajeros de la Tierra (Prayer for the Old Voyagers of Earth),” Star*Line 46.1

- A Belief in Cosmic Dailiness: Poems of a Fabled Universe (chapbook, Red Ogre Review)

Prompt of the month

Write about something that gives you as a writer, your characters, or your poetic subject comfort. When we’re writing about other worlds, whether that’s a medieval Earth or a future planet, think about what is comfortable. What does contentedness or happiness look like for your characters or yourself? It doesn’t necessarily need to be cozy. Where is the dailiness, the mundanity?

Links mentioned

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s “ansibles”

- Strong Women – Strange Worlds (reading series)

- Arthur C. Clarke

- The Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association (SFPA)

- Virginia Woolf’s Room of One’s Own

- Un hueco en la luz by Amanda Junquera (essay on this work by Angela at Flying Island)

- Mundos al descubierto (Spanish short story anthology)

- Ángeles Vicente

- Emilia Pardo Bazán

- El laberinto del fauno / Pan’s Labyrinth (movie)

- El espinazo del diablo / The Devil’s Backbone (movie)

- El bosc / The Forest (movie)

- Becky Chambers

- Valerie Valdes

- Vicente Aleixandre

- 2023 Utopia Award Nominees

- The 2023 Rhysling Award Anthology

- Guidelines for submitters to Eye to the Telescope’s “Food & Feasting” issue, ed. Claire McNerney

- 2nd Annual Sturgeon Symposium (held Sep. 2023; feat. Angela Acosta and Angel Leal on the virtual roundtable “Latinx Speculative Poetry Futures“)

Episode Transcript

BH: Welcome Into the Looking Glass, a podcast created by Jasmine Arch for speculative poets and poetry lovers alike. I’m Brittany Hause, pitching in as co-host for season two of the program. I invite you to join me, Jaz, and this year’s guests on a journey into a world where nothing is what you expect it to be. Together with speculative poets from around the globe and from all levels of experience, we’ll be exploring the magic behind this fascinating genre and hopefully have a few laughs along the way.

For this month’s episode, we’re chatting with Angela Acosta.

Angela Acosta is a Latina poet, translator, and researcher of Spanish literature who grew up in the state of Florida. She’s earned several degrees in Anglophone and Hispanophone literary fields, including, most recently, a PhD in Iberian Studies from Ohio State University. Her latest academic investigations, teaching, and creative writing endeavors all aim to shine new light on the work of early 20th-century Spanish women authors.

Verse translations and articles by Angela have appeared in Metamorphoses, Ámbitos Feministas, Feminist Modernist Studies, and elsewhere, and you can read her original poetry in both Spanish and English in Space and Time, Radon Journal, Apparition Lit, and numerous other publications online and in print, including in her 2022 collection Summoning Space Travelers and her 2023 chapbook Fourth Generation Chicana Unicorn.

Welcome to the podcast, Angela.

AA: Thank you so much. It’s great to be here.

BH: It’s really great to have you on. Before we get going, could we hear you say your name as you would pronounce it, in your own voice, and also could you let us know what pronouns you go by in the third person?

AA: Absolutely. My name is Angela Acosta [ˈændʒələ aˈkosta] and I use she/her pronouns in English, or if we’re talking in Spanish, we can use ella.

BH: Hm. The academic side of your work’s taking you into all realms of fiction and nonfiction, not only poetry. We’re going to be concentrating on poetry, because this is a poetry podcast, but you do have a lot going on in different literary spheres, as we just heard about a little bit.

I’m especially interested in your own writing that touches on sci-fi tropes, on things that veer sort of science fiction-ward, so I do want to talk especially about your poetry collection Summoning Space Travelers today. That’s the one that I’ve got my hands on, so I’ve read through that one, and I’d especially like to talk about some of the poetry you have in that collection that’s set in technologically complex sci-fi futures, because there’s quite a bit of that in that collection.

What kind of fascination does the idea of these futures with very complex forms of technology that we don’t have available today—and interplanetary migration, as well, is a recurring theme in your work and in this collection—what fascination do those topics hold for you?

AA: Yeah, I’ve always been really interested as a reader in science fiction and the possible and ansibles and Ursula LeGuin’s ways of creating all of these different worlds, from writers who are just focused on the solar system. So that’s always been an interest of mine and now it led me to writing speculative poetry.

I didn’t start writing speculative poetry until about two years ago, so summer 2021, basically. I didn’t really know what was out there and then I found the Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association, and I suppose the rest is history.

So, it’s always fascinated me to think about astronomy, think about the possibilities of space travel. And having grown up in Florida, seeing space shuttle launches on a regular basis, just wanting to be part of that future, wanting to see what could be on other planets if we were able to travel there, have generation ships take us places. But also a deep interest in making sure that these ways of getting off the earth are equitable, and aren’t damaging to the planet, and things of that nature.

And the beautiful thing about writing poetry that might differ from fiction is you don’t need to have all the details worked out, necessarily, in terms of tinkering with the technology as one would if you were writing a fiction story or novel. You can introduce these concepts without necessarily having the deep research or the deep conversations about [things] that characters of fiction might have.

BH: Yeah, there’s quite a few poems in Summoning Space Travelers that almost, to me, read like sort of mini-essays. As in, like, nonfiction essays, that use a lot of the wording or the vocabulary of sci-fi that you would expect in reading a sci-fi novel or a sci-fi short story, but that really take [up] contemporary concerns…

And it’s speculative in the sense that you’re speculating, you have a lot of questions you’re asking about where things might go, but not necessarily sci-fi in the strictest sense, because some of the poems in this book, they are very much couched in the here and now, and the speaker could be you or someone with a life experience very similar to your own who’s asking these questions.

Other poems in the book are definitely explicitly sci-fi, however, so I’m going to want to talk about those, as well.

When you mentioned Florida entering into your fascination with space travel—yeah, I had noticed that in Summoning Space Travelers, Florida pops up as a setting and as—in the case of some of the poems set in the future—as a remembered home, in the past. Aside from the NASA programs that are going on in Florida, is there anything about Florida that makes it an especially sort of fertile ground for speculative writing for you?

AA: That’s a good question.

You know, I started in high school writing a lot of more contemporary-leaning poetry, and having grown up in Florida there was a tendency to kind of couch things into what it’s like to live there, specifically, with the environment, and ecology, and just the uniqueness of the fauna and flora and I think, kind of like writers like Arthur C. Clarke focused on Sri Lanka, you just kind of focus on your own lived world, what you’re inhabiting, especially if that world is perhaps different geographically or environmentally from other places.

But I think the main draw in thinking about it is NASA and rocket launches and also that question of the Anthropocene, and will Florida go underwater in however many centuries or millennia or however long it takes.

BH: Yeah, I seem to remember that there’s some parts in the book where you draw some interesting connections with Florida’s colonial… indigenous, and then colonial… past and the idea of, you know, space travel and colonizing.

Even though we’re talking about worlds that presumably don’t have life on them before the humans arrive there, still there were some parallels you were drawing, some kinds of questions you were asking about how the process of moving out into the stars and moving into these new places where we haven’t lived before—as the human race, you know, talking about just humans in general—how that might be similar and different, you know, in various ways to what went on in Florida’s past, and in South America, and other parts of North America.

And, yeah, I was wondering if some of that sort of came up for you the first time as you were writing this collection, the poems in this collection? Or is it something that you’ve been ruminating on for a long time, the sort of connections between the past and where we’re going in the future, you know?

AA: Yeah, I think the question of place is especially important in, kind of, in my overall goals of trying to see how these diverse cultures can be represented and brought into space, brought into different centuries in the future, whether that’s on Earth or elsewhere. I’m really interested in, then, the history of these places on Earth.

… the question of place is especially important […] in my overall goals of trying to see how these diverse cultures can be represented and brought into space, brought into different centuries in the future, whether that’s on Earth or elsewhere.

So as you were talking about Florida, I was reminded of another poem that isn’t in the collection. It’s a bit more recent. It’s called “Paradise of the Abyss,” from the Mithila Review, and it’s basically this new environmental, ecological landscape in a city called Paradise of the Abyss that’s part of the Yucatan Peninsula, and thinking about how we can create a greener, more equitable world in that unique region of the world, which I haven’t actually visited, but is a place of much fascination and definitely a setting of a lot of novels, speculative or otherwise.

BH: I haven’t read that poem that you mentioned, but I’m going to go check it out after this, because, yeah, that does sound like it just takes further some of the themes that you developed in your book, and very much in line with some of the questions you were asking, and sort of partially answering, although it doesn’t really seem like this is really a book of answers so much as it is of questions. You have a lot of questions that don’t really get a solid concluding, final answer. But that was one of the things that for me made this a really interesting poetry collection to read, was it seemed to me like many of the speakers in this book were not in agreement with each other. There were some that looked at things in one light as others who seemed to look at it in, actually, a completely contradictory light.

In the beginning of your book, in the first section, there is a poem—“One Planet People”—[which] has a speaker who is very adamant about remaining on planet Earth. This is our home, and this speaker is very resistant to the idea of leaving and trying to establish humanity’s salvation or whatever elsewhere in the galaxy, as, you know, interplanetary travel is sometimes presented as the end-all, be-all solution to our current problems on Earth, and this this speaker takes a very hardline rejection stance to this notion. And they say at one point here, “We reject plans for Dyson spheres, generation ships, and cryogenics, / throwing away the key before you get any nefarious ideas.”

However, in later sections of the book, and even in the first section, there are definitely speakers who are on generation ships and colonies out on other planets in space who do not take this sort of view at all. So, I was wondering, when you were writing this book did you have in mind this sort of back-and-forth among speakers? Or was it something that sort of just arose from all the different speculative—in the sense of wondering—pieces you were writing individually?

AA: That’s a great observation.

I don’t think I necessarily had the sense of dialogue, but I think in creating the different sections of the book—so that that poem coming from the Terran Born section, or the Earth-based section, and then later having Outward, We Sojourn, going into space, thinking about that journey, and then ending with [the section] Summoning Space Travelers and more distant futures or more established worlds—I think for me, it’s a very philosophical book and kind of taking from the questions I have, or the quandaries that characters face in science fiction novels that I’ve been reading for many years.

And so I think that that contradiction was definitely intentional in the sense that there are no cut-and-dry solutions right now, and how to responsibly create these futures if we do have the technology to do so.

So, like with “One Planet People,” it’s being very aware of the impacts, the environmental impact and the engineering that goes into creating these rockets that can go elsewhere, but also realizing that it’s not necessarily our salvation, like you were saying.

And I have a poem that was published in Dreams & Nightmares called “A Refusal to Be Starborn,” which also takes on that question of not wanting to colonize space and wanting to be responsible for the Earth. And then other voices in this collection, going beyond that and kind of reconciling the environmental and the technological, or they live in a different century where then those decisions have already been made, and then thinking more critically about what’s been left behind and forgotten.

I should also add that the collection itself—and I started with the name of the collection, Summoning Space Travelers, and at first, I thought it was going to be this collection of aliens and, you know, these other non-human beings—but then, in writing the poems, I realized that it was more about writing to future humans, or future versions of sentient beings who will be making these decisions and will be living in ways different than our own but with similar preoccupations and similar social problems, social stratification, cultural differences, linguistic barriers, things like that nature, rather than sticking with what I first thought of as being literally the alien, right?

BH: Yeah, do correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t think there’s a single poem in the book that’s written from a point of view other than human. It’s all human, right?

AA: Right, it’s all human, exactly.

BH: Yeah, and I thought that was a really nice sort of thematic thread that tied the whole thing together. Even though there was all this disagreement among different speakers about where we should be going from where we are now, or in the case of the future speakers what they should be doing in those sci-fi futures that they’re speaking from, I did see that there was an Earth, a human connection for every speaker.

Actually, when I started reading the collection because of that title, Summoning Space Travelers I was kind of, like, surprised when I first started reading, because I thought, “Well, this is all sort of set in the here-and-now, more or less.” And then when I got into Section 2 and Section 3, I said, “Oh, okay! There’s an arc. There’s sort of a progression, and now the title of the book makes sense.”

But at the beginning, with poems like “One Planet People,” I thought, “Well, this doesn’t really sound like a summon[s] for space travelers. [It] sounds like an anti-summons for space travelers.” But, yeah, no, as the book goes on, you get more and more of that sort of back-and-forth that I did find very interesting, all along with this connection to Earth.

So I think that was a good narrative decision. [It] could have turned out nice with aliens and all the sci-fi kind of themes that you had in mind at the beginning, but I think this really ties the whole book together very nicely.

You’ve already mentioned two poems that you’ve written on similar subjects to the ones that you tackle in this book, but do you have more poetry that explores the ideas of Summoning Space Travelers in the works? Are there other ones you’re working on right now that look at these kinds of ideas?

AA: Yeah, although I think right now I’m focusing a little bit more on narrative-based poems and adding more characters to these poems, so that they can kind of function as these kind of flash pieces of life on a space station, or the relationships between these characters, so moving a little more towards that and a little bit farther away from these, like, philosophical questions that are in the collection.

So I think my work that I’m in the process of publishing and the chapbook that I’ve been submitting have a lot to do with imagining these possible worlds for queer, Latinx, people of color, people who don’t speak English, what does it look like to make space accessible for people, especially [those with] physical disabilities?

So those sorts of questions lead me to thinking then about characters… and so the collection that I’m working on now, that I’m in the process of submitting, has a lot to do with similar concerns as Summoning Space Travelers, but at the same time [the poems are] a little bit more narrative-based, a little bit more focused on particular slices of life and scenes from other planets.

[It] will still be very human in focus. So, like Summoning Space Travelers, there’s a few poems that use Spanish or were originally written in Spanish, but there are a few non-human beings that do create plot in these other poems that I’ve been working on.

BH: Hm. I know you have at least one short story in Somos en escrito, right, that you published about inhabitants of a generation ship, or one ship in a generation ship fleet, right?

AA: Right.

BH: And I guess that sounds very similar to the poems that you’re writing now, that you’re working on. As you’ve just described them. It’s a narrative dealing with space travelers who are from a Latinx, or Spanish- and English-speaking background—there’s a lot of code switching, a lot of discussion of the role of English and Spanish on this ship, which is quite interesting.

What was the name of that story, again? I’m blanking right now.

AA: Yeah, it’s “May We Be Named.”

BH: “May We Be Named.”

AA: And it’s in Somos en escrito. It’s kind of a science-fiction love letter to all of the Latinx diaspora who struggles with losing connection to their language or their histories in many different ways, right? And wanting to write a story in which we’re not just obsessing over these lineages and family trees, but really feeling comfortable with what we don’t know, and feeling comfortable with these communities and identities that have formed over time, and gaining a stronger connection with the people around us and especially with elders as they appear in the short story, and asking them about how things were, and what they were called, and things of that nature.

[I wanted] to write a story in which we’re not just obsessing over these lineages and family trees, but really feeling comfortable with what we don’t know, and feeling comfortable with these communities and identities that have formed over time …

So I don’t want to spoil anything about the story, necessarily, but those were kind of the main concerns I was thinking about. Because it is true that a lot of folks think about their background and what they do know, the ancestry they’re aware of, the languages their ancestors might have spoken, or if they do speak the language, perhaps it’s a different dialect, different words are used, you know… Things are constantly changing.

BH: Yeah, and I really enjoy in that particular story—which I also don’t want to spoil the plot of any more than I already have—but the use of code switching, or going back and forth between Spanish and English, sometimes just a word dropped in here or there, sometimes whole phrases or sentences in one language and then in the other, spoken by the same character, it really bolsters, kind of really emphasizes the point that you’re getting at with the entire story, and it really drives home some of the ideas that you’re exploring in that story.

And I think even for people who don’t speak any Spanish, the way you handled it, I believe they should be able to navigate the story and understand more or less what’s going on, despite the bits of dialogue that are presented in Spanish. Or, if not, you know, maybe they can ask a friend or use Google Translate.

AA: I’ve been sending around a completely English translation PDF, because I read part of that story for the Strong Women • Strange Worlds reading in May.

BH: Uh-huh.

AA: So then [to] folks who are interested, I’ve sent along the fully English version of the story.

BH: Oh, was there requests—did they find it difficult to fully get into what was being said without—

AA: Oh, no, they just asked if we had anything for a giveaway. So my giveaway was just to share the full English version, since it’s not available online.

BH: Oh, okay. That’s interesting. Yeah, I feel like the reading of the story would be very changed with the full translation to English!

AA: Yeah.

BH: Because a topic, a central concern of the story, is language and how it’s used, and what kinds of connections it has to hierarchy and power structures, and this sort of thing.

AA: Mhm.

BH: And, yeah, the way that you aligned the dialogue, the language in the dialogue, with the topics you were tackling, I thought was very effective. But, yeah, I wonder how the story would change reading it only in English, or only in Spanish, for that matter.

AA: Mhm.

BH: But I would encourage people to give it a try as it is presented on Somos en escrito. And if not, now we know! There is a fully English version for people who feel a little daunted by the idea of reading a story with bits in Spanish, if they’re from purely Anglophone backgrounds.

But, yeah, so, the poems that you’re working on with a sort of more narrative structure, they align in sort of overall intent with that story? You have the same kind of goals, same kind of narrative ideas in mind as you’re writing these poems that you’re working on now?

AA: Yeah, a little bit. I think, in general, they have to do with representing Latinx lived experiences in space, and not necessarily of a particular cultural background.

With “May We Be Named,” it’s for a publication that has a lot of Chicanx writers, Latinx writers, but I don’t necessarily write it like that, because that’s not my own lived experience, of having been deeply immersed in one particular Latinx culture.

So it kind of varies. I also have a lot of poems that are working with different relationships between people, whether they’re romantic or platonic in nature, just seeing how these relationships play out in different contexts. What do we do when our partner is sent away across light years, and we can’t interact with them, and our ages are going to change? Or what happens when we decide to settle down on a space station together, right? What does that look like?

What do we do when our partner is sent away across light years, and we can’t interact with them, and our ages are going to change? Or what happens when we decide to settle down on a space station together…?

I recently published a poem in Utopia’s June/July issue called “T & R Used Books & Curios” which is about a book-and-curio shop that’s on a space station.

BH: Wow, there’s a lot of poems you have out there that I wasn’t aware of! I should have done a little more background research before we started this episode, but that’s another one [that] sounds very—

AA: Well, these are very recent publications. Like, in the last few weeks. So, yeah.

BH: Oh, I love that idea, though. Just anything that sort of combines what we might think of as almost antiquated…

Of course, there are bookstores still now. Of course, they’re around, but—

AA: Mhm.

BH: Bookstores sort of, for me, have associations with traditions of the past, when we’re talking about, like, brick-and-mortar bookstores. A lot of people turn to ebooks or audiobooks or online shopping for their bookstore kind of needs these days. And so bookstores, for me, have this sort of feeling of being tied in with our past and our communal traditions.

So combining that with an explicitly future setting like a busy space station… I really just enjoy the concept before even getting any further into the poem. So I’ll have to look that one up! That’s on Utopia, you said?

AA: Yes.

BH: That publication focuses specifically on sort of optimistic outlooks, right? Hence the name?

AA: Yeah. It’s also the Pride issue for June/July, so we’ll see poems and short stories that are more in that direction, of representing queer possibilities in space.

BH: Right. Ok. Yeah, it seems to me like a really good publication to check out for less of a downer sort of side of sci-fi. Which I think…

This is a more recent publication? It started up more recently, I believe? Because they have their Utopia Prize which is only in its second year.

AA: Uh… yes. Yeah.

BH: I can see why they felt like there might be room to like carve out a little extra space for upbeat, happier kind of sci-fi.

Because with many things going on in our world today, as it is now, I understand why people tend to gravitate towards less optimistic kinds of futures in their writing. But sometimes you just want a kind of pick-me-up sci-fi story, if sci-fi is what you gravitate towards. So I I’m going to be checking them out a little bit more in the future, too.

AA: For sure.

BH: I did see that your poem “Tamales on Mars” is nominated in the second annual Utopia contest in the poem category.

AA: Yeah!

BH: I have yet to go back through and read all the nominees aside from yours. But I can definitely see how your poem fits the bill, because “Tamales on Mars” is a very optimistic, a very, like, light-hearted, positive look at what could happen in the future, what interplanetary travel could be, and what would be one of the better outcomes of that kind of adventuring.

AA: Mhm.

BH: And that is a poem that’s also included in Summoning Space Travelers, just in the second section, after we start branching out a little farther.

As we already mentioned, quite a few of the poems in the first section, especially, of this book, they’re set in the present day.

AA: Mhm.

BH: And they aren’t especially sci-fi in concept, even if they use quite a lot of wording that is reminiscent of works of sci-fi.

There are a couple of exceptions, because I would say that in that first section, we’ve got “Life Capsule,” [which] definitely appears to be written by a speaker in the future. They mention that forests felled in the 2040s were used to make the paper for a book that they’ve included in their capsule. So we’re set in a future sort of ambiguously beyond our own.

But other than that one, I would say most of them could have been spoken by people in the here-and-now, whether it was you or someone who has similar experiences to your own. But then after that, later in the book, we start getting into more and more explicitly, obviously sci-fi territory.

And so I was wondering as you went about creating this book, weaving these poems together for this collection, how did you go about choosing which of these pieces you were going to include? And then what determined the order of presentation for you in the end? How did you decide to divide it up into these three sections and organize them in the way that you did?

AA: Mhm. Yeah, so like I said earlier, I really only started writing more speculative-tinged poems about two years ago, so this is kind of the first round of that. And early on, in going in that direction, I knew that I wanted to write, whether that be a collection or just a packet of poems, centered around these themes of “summoning space travelers,” and what concerns do we have now, how will these we addressed in the future, what will life look like on Mars or other planets.

So I just started writing and submitting these poems. So, compared to the collection I’m submitting now, this collection has a lot more poems that were already published in science fiction magazines or, in some cases, magazines that include speculative work but are mostly literary, contemporary poems.

I liked the idea of naming the different sections of the book, because I saw this trend, like you see, of being on Earth and then moving outwards. And so I’ve kind of moved the poems along as I’ve seen fit.

For example, the last poem in the collection was certainly not written last. It was one of the earlier ones, but I thought it served as a nice sort of coda of the writer addressing her own work and her own remaining questions, right? That I and others might still have.

So I named the different sections and then, from there, I created the two poems that are the same as the section titles, so “Terran Born” for the first part and then “Summoning Space Travelers” for the third part, as a way of bridging these different sections.

In many cases, I had poems that were previously published that might have been together. So, for example, “Life” and “Tesseract,” in Part 3, were both published in MacroMicroCosm, so I wanted to keep them together.

So there were some poems that were written for different publications, or met the goals of different publications, such as wanting [a] more positive, optimistic outlook or wanting specifically queer or crip readings of space, that found their way mainly into the third section of the book.

So that was kind of the direction I chose in putting them together. I didn’t necessarily have a fixed strategy. I wanted a more or less equal amount of poems in each section, and just kind of played around with a different order as I saw might work and placing poems that spoke to each other next to each other, especially with the poem “Ad Astra, Our Motto,” which appears in English and Spanish, so you know, of course keep those together.

BH: Mhm. Yeah, just as you were mentioning in the third section trying to involve more explicitly queer and crip readings of these sci-fi topics, I noticed that you have “Our Queer Home in Space” followed immediately by “Cripping Outer Space.”

AA: [Laughing.] Yeah.

BH: Yes. It is definitely very overtly there.

In “Cripping Outer Space,” the speaker says, “I want to crip outer space, / send up fellow travelers / trained with breathing apparatuses, / armed with knowledge of machinery.”

Could you just tell us a little bit more about what “cripping outer space” would… I mean, yes, you discuss it in the poem, but could you elaborate a little bit on it for us, this idea that you discuss in the third section, especially?

AA: Definitely.

Yeah, I would love to write more on this topic.

So this poem was originally published in Wordgathering, and I wrote it because there’s a lot of physical limitations for folks who want to go into outer space, beyond just the regular challenges of becoming an astronaut. You need to be of a certain height, there’s some other regulations for health reasons they put, right? We only have so many space suits, if you’re too tall or too short you can’t go in them, and there’s many other things that make it difficult for most people on this planet to go into outer space currently and will continue to be a challenge moving forward. And this, you know, this idea of the able-bodied, male, white astronaut, how do we expand that narrative to be able to move more freely, to be able to stop having that disparity [in] who is able to explore beyond Earth?

… there’s a lot of physical limitations for folks who want to go into outer space, beyond just the regular challenges of becoming an astronaut. […] How do we expand that narrative…?

In my own lived experiences, knowing that I myself am not going to be able to go into outer space, and of having a respiratory condition and not being able to do some of these physical things that astronauts, in particular, would have to do, and kind of going along with what I’ve been writing about in terms of Latinx futures and how do these cultures, how do these lived experiences find their way in a more just future than is currently available, right? And kind of making the argument of this poem saying that we can go into outer space and people with especially physical disabilities are very much able to, it’s just a matter of making things accessible. And actually those people are the ones who are most likely to be able to navigate those sorts of new mobility aids, new ways of just doing basic daily things, whether that’s, like, you know, self-care or eating or things like that.

Everything is more complicated when it’s zero gravity, so yeah.

BH: Yeah, just now, it just occurred to me, as you were talking about the space suits in particular, I remembered that in a poem that appears earlier in the collection, “Gift of [the] Ancestors,” there’s someone who “refused to cut her braids / to fit into a regulation sized spacesuit.”

So there’s physical limitations that you need to have this technology to be able to work around. In this case, we have someone who others might argue, you know, “It’s optional. She could cut her braids.” However, she doesn’t regard it as optional.

So yeah, I do think this is… whether we’re talking about strictly, like, physical limitations on mobility and that sort of thing, or if we’re talking about elements that are determined by culture and, like you were saying, a lot of this was designed to be accessible to white men, who are expected to have short hair, for example.

It is something that comes up in a number of different ways in this collection, and I hadn’t been drawing the line between “Gift of the Ancestors” and “Cripping Outer Space” until right now. But, yes, there are many reasons why someone might not be able to utilize the technology as it has been designed currently. And, yeah, there’s a lot of need to work on that if we’re going to get more than one very specific sort of person involved in this exploration and outward movement and various kinds of innovation that you discuss.

AA: Right. And it’s one thing to have stories where people of, you know, different cultures and abilities, or different aliens, have these spacesuits and they’re all set and ready to go in their rockets, but it’s also like, how do we get there, right?

We ask the question of, like, how do we get to that future where it’s quite simple to adjust things and quite simple to, you know, have EVAs in zero gravity.

BH: Hmm. I was wondering as I went through and read about all of these future-world kinds of topics that you’re tackling whether any of the writers that you’ve looked at academically—because you have your whole academic career where you examine the work of writers from Spain and from other Spanish speaking countries, but for the moment your focus has been on Spanish women writers, especially—are there any writers whose own work looks into sci-fi, horror, or fantasy, these genres?

Are there any people whose work you’ve been analyzing who kind of dive into these areas, these genres of literature?

AA: Yeah, so my area of research that I’ve been working on both in the dissertation and future projects has been early 20th-century Spanish writers, especially women writers.

There are some up-and-coming scholars who have done really great work on the speculative, especially in Latin America. I don’t necessarily focus on those genre[s of] fiction, because it is a bit… you know, first of all, labeling it as such a hundred years ago does get a little bit tricky. But also just not necessarily reading the contemporary speculative, science fiction work coming out of Spain and Latin America as regularly.

…what I’m interested in is the possible worlds that the women writers I’m reading and writing about are creating and engaging with, […] thinking about how do these writers carve out space for themselves, for their different identities…

So, for me, what I’m interested in is the possible worlds that the women writers I’m reading and writing about are creating and engaging with, and moving beyond, you know, Virginia Woolf’s idea of a room of one’s own, and thinking about how do these writers carve out space for themselves, for their different identities, whether that’s through travel writing, whether that’s their somewhat surrealist-tinged poetry, whether that’s through semi-autobiographical work, as it might be called, or just novels that engage with what it was like to be gay and a woman in the early 20th century.

So all of these things lend themselves to speculative genre, even if the plot itself is based on Earth and not any bit abnormal.

One of the collections that I worked with that isn’t regularly studied at all because it hasn’t been reprinted since it was first published in 1947 is Amanda Junquera’s Un hueco en la luz, A Gap in the Light. It’s a collection of short stories and the titular short story, “A Gap in the Light,” deals with this woman who’s a mother and is very tired with her daily routine. And she has this whole half of the story imagining what life would be like, using this subjunctive, talking about if only she were sick, she would be able to be cared for by other people, and she would have this marvelous day, and her husband would be loving and affectionate towards her. And then we’re hit with the reality of what things are really like in the second half of the story.

So the way she plays with the subjunctive tenses and talks about this possible world, only to be thrown back to start the real one, is very much in line with what speculative writers today are still thinking about, of what is possible inhabiting these bodies and inhabiting these particular identities.

But in terms of specifically science fiction works, there’s an anthology that I really like that I guess would be called in English Worlds to Be Discovered. So it’s Mundos al descubierto: antología de la ciencia ficción de la Edad de Plata, so science fiction from Spain’s Silver Age, 1898-1936, organized by Juan Herrero Senés. So that does have very science fiction stories.

What I like about it is that these writers are the writers that folks would know from this time period, that are typically seen as just doing contemporary short stories and novels, but they actually do have selections that are science fiction in nature.

So I gave a conference talk on one of them, being Ángeles Vicente’s “Absurd Story,” or “Cuento absurdo,” about a mad scientist who’s an anarchist and wants to destroy the whole world. There’s another story in the collection by Emilia Pardo Bazán, a very renowned writer spanning both centuries, who writes about people living in caves, I believe.

So, taking the writers that we see as contemporary and finding the moments where they’re going into the speculative, and going specifically into science fiction, whether that’s through the tropes, technologies, or other reasons.

BH: It sounds like, even with the authors who don’t go as far into what we would recognize as being the science fiction kind of realm of things, among those Spanish women you were talking about who you are especially focusing on at the moment in your investigations, there’s a lot of overlap between the kinds of concerns that you’re looking into and the things that you discuss in Summoning Space Travelers, even if in Summoning Space Travelers you’re looking at it through a sci-fi lens. It sounds like this idea of carving out a space where there wasn’t room for a particular kind of person before is a very sort of front-and-center concern both in your research and in the matters you discuss in Summoning Space Travelers. So I could definitely see an overlap there, even if it’s not explicitly cast in sci-fi terms or sci-fi in concept in the case of the writers who you’re focusing on at the moment.

Is there anyone in addition to that sci-fi collection that you just mentioned—which sounds like a pretty great resource—is there anybody in particular that you wish that people who are interested in speculative verse, speculative poetry in particular knew about, was more familiar with, that you think would be of interest to people who are readers of horror or fantasy or sci-fi poetry?

AA: Hm, that’s a good question. I think it’s hard to answer because one would need to be able to read them in Spanish. Most of this work is not available in translation.

But I think there definitely are some interesting early 20th-century stories that I think it’s worth tapping into [in] the Latin American and Spanish canon as a writer today. So I don’t necessarily have any specific recommendations, but I think they’re definitely there, and I think when it becomes available in English, it’s a great resource.

BH: When you do classroom teaching—because that’s yet another thing that you do quite a bit of—do speculative genres make their way into the curriculum in any way? Have any of these sci-fi- or fantasy-leaning kind of stories or writing made their way into your classroom teaching?

AA: Not yet. The classroom teaching I’ve done up until now has been me as an instructor of record, but ultimately having course coordinators helping design the syllabus, or looking over the syllabus, or me following a syllabus created by a different professor. So I haven’t necessarily been able to introduce speculative works, since my goal is mainly to introduce works that might be taking place during the Franco dictatorship during the Spanish Civil War.

So I think I’m thinking about your previous question about science fiction, horror, fantasy… I think there’s a lot that can be found in representations of the Spanish Civil War throughout the decades, and the fascination with the fallout of the war, the many people who were buried in unmarked graves and still can’t be found…

[Speculative genre elements] can be found in representations of the Spanish Civil War throughout the decades, and the fascination with the fallout of the war, the many people who were buried in unmarked graves and still can’t be found…

That really started up again in the early 2000s. So things like Pan’s Labyrinth, those sorts of movies that are engaged with that historical memory, but also still rooted in horror or science fiction genres, are especially interesting in understanding the reception of these historical events in the present day and also how these genres are taken up in Spain.

I remember one of the movies that I watched was, I think, originally a Basque film—or sorry, a Catalan film. It had a Catalan name. And it had these fish from another planet that appeared, so it was very weird, but these sorts of things that appear as ways of representing symbolically what occurred, or ways of not showing the violence directly, but through other means, are very regularly apparent in Spanish films that depict the Spanish Civil War, or allegories of the Spanish Civil War.

BH: You’re saying, not so much explicitly sci-fi, but there’s definite correlations to the kinds of things you would discuss in a sci-fi frame? Is that what you were getting at—with the Civil War, there’s a lot of discussion of possibilities…

AA: Yeah.

BH: …whether or not they veer into the realm of sci-fi? Right. Ok.

AA: Yeah, so basically these films that use allegories and symbols to depict the violence—or a bomb that has fallen and is staying put, but this bomb that’s fallen, and we have ghosts.

The Devil’s Backbone, El espinazo del diablo, for example, tackles that particular moment, but also this kind of alternate timeline of that historical period, which is particularly interesting.

And then the other film that I was thinking of that I watched several years ago was called The Forest in English, and it’s about the Spanish Civil War [that] has broken out, but then there’s these strange creatures that come and go from the forest, and it’s very strange to see that juxtaposition of this very historically based time of the 1930s with these other creatures, or these kind of strange ways—like as done in Pan’s Labyrinth—these strange creatures that appear as helping especially children process the traumatic aftermath.

So I think that’s been a very fertile ground for science fiction reimaginings of that time period that has very much been in the cultural imaginary of Spain in the 21st century.

BH: Hm. Yeah, Pan’s Labyrinth… it was difficult all the way through—intentionally so, I’m sure—to determine just how much of the fantastical elements we were seeing were meant to be interpreted as real-life features of the plot, things that were actually occurring, versus things that were representations of what was going on in the protagonist’s mind.

And I’m sure there’s a lot of that kind of ambiguity all throughout the other films you’re speaking of, even though I have not seen the Catalan movie that has the fish from outer space you mentioned! That one is unfamiliar to me, but it’s something that certainly occurs in a lot of short stories from Spain and also from Latin America that are coming to mind from the early 20th century. There’s a lot of ambiguity as to just how much we’re supposed to interpret something literally or not, plotwise, in the narratives that we get discussing climactic cultural changes or social issues.

AA: Which can make it difficult to teach.

BH: Oh yeah, I imagine! No, I imagine. Yeah.

If you were going to design your own syllabus, your own curriculum, whether sci-fi or not, what would be sort of your dream syllabus? What would you really like to teach if you just had your own say in every part of the classroom experience?

AA: Yeah, I’m actually designing my own syllabus now for a course I’ll be teaching at Davidson College in the fall on modern women writers. So, focusing on… basically, focusing on life-writing of women writers of the early 20th century, as a way of introducing the literature, history, and culture of Spain from that period.

And, of course, I can’t include everything because the autobiographies can be quite long, but, you know, it’s anything from a diary written by a Spanish painter who traveled all over, but was still dealing with some inner turmoil and depression, to travel logs of writers who went into exile. I mean, there’s a huge diversity in writings from this time period that are still being found as found manuscripts, are still being published as such.

I know I’d love to hear some recordings of these women writers. One of the limitations is that their interviews [are], many of them, done in Catalan, which is a language I don’t speak. So there’s so much that can be put together for a course, or put together for one’s own research on the topic. So I’m looking forward to getting a snapshot of that time period through short stories, novels, and other sorts of text that we’ll be reading in the class.

BH: That’s very interesting, that a lot of the women writers who you’re talking about were Catalan speakers who were writing in Spanish. Was this because they were publishing in Spanish at the time? I had imagined their personal writing would veer more—

AA: Oh, it’s not so much that they themselves are Catalan. It’s just the grouping of women that selected for those interviews were based in Catalunya and were Catalan writers. So, many of the writers I study are actually Madrid-based Castellano speakers. I just meant for the ones interviewed in that particular context, the interviews were done in Catalan, but the writers themselves… there’s a big focus on Madrid as a city inside of many of these novels and short stories, actually, for Castellano literature.

BH: Right. Ok. When you mentioned the Catalan interviews, I was thinking about the Civil War, and the sort of marginalization of languages other than Spanish, or Castellano—

AA: Sure.

BH: —as you’re were saying, yeah, and the recurrence of that as, like, a pretty important theme in Civil War writing.

But, yeah, no, that would be a class I would enjoy taking, because there’s an awful lot I’ve not read from Spain, and especially from women writers! I believe that most of the writing that sort of makes its way across my dashboard or my desk in one form or another from Spain tends to be by men, especially if we’re talking about pre-21st century. Without seeking out women writers, I wind up coming across writing from men.

So that would be a very interesting thing to learn more about, and I’m sure you’re uncovering a lot of things that your students would never have heard of, so it must be a really eye-opening class.

You said you’re going to teach that next semester?

AA: Yes.

BH: All right. Good. It’s going to be a reality, not just a speculative class.

AA: Yeah. Exactly.

BH: You mentioned that a lot of the work that you study, it envisions possible queer female futures for the speakers, or for the narrators, of the writing that you’re looking at. And you’ve talked about that a little bit already, but I was wondering especially about the queer element here, because I’ve been hearing a little bit about, you know, opening a space for women in a society that’s very sort of male-oriented, or you know masculine-elevating, but I was wondering about the queer futures that you mentioned to me, and what sort of liberating possibilities beyond the bounds of Earth, or beyond the life as they know it at the time of writing, would you be thinking about, would you be discussing here?

AA: Mhm. Yeah, so in the case of, like, my own research, I think what I’ve been focusing on lately has been a lot about the double marginalization of women writers who may not identify as women, or may not identify as heterosexual, and having that ambiguity in their gender identity and sexuality, or rejecting a label altogether, but wanting some sort of future different than the one that’s been imposed on them is very much present in a lot of the work that I am reading.

Even if it’s a story where the housewife decides she’s going to go back to devoting herself to her husband and her children, she’s still left with this ambiguity of seeing another world that is possible, or knowing what she would desire if only she could live that future that’s not available to her. So that very much influences my own poetry, and my own way of understanding speculative fiction, and the goals of reaching queer female liberation, whether that’s through creative work, activism, things like that.

So it’s very much on my mind, the ways that I’m engaging with these questions in an academic context and the ways that it gets presented in speculative writing. I think it has everything to do with contemporary science fiction writers like Becky Chambers, who brings in that element to her writing, or even Valerie Valdes, who brings in her own experiences—Cuban-American, bringing in the Spanish in her writing—seeing what other writers have been able to do, it’s been really phenomenal, because I mainly was reading male-authored science fiction from many years ago, as a child and mainly teenager.

So it’s kind of nice to have the companionship, whether that’s, you know, through online connections and literary magazines, to reading their works themselves.

BH: Yeah, so we already mentioned that there’s a pretty large, noticeable overlap in theme, or in thematic focus, between the works that you’re researching and your poetry, the sort of topics you’re exploring in your poetry, but I was wondering, is there any other way that the work of the writers that you’ve been researching has influenced your poetry, your own writing, that you can identify?

AA: Mhm. I think another topic that we’ve not quite spoken about, but sort of hinted at, is the question of the archive, and the question of physical artefacts.

I think physical artefacts play a role in some of the poems that I’ve written in the collection, and especially poems since then, where I’m questioning what will artefacts be of this time period, how will things be preserved is a great preoccupation of mine, as a researcher whose work is based in the archives, and trying to find what is available and reckoning with what is never going to be found, whether that’s because it’s been destroyed, or will one day be destroyed, kind of both ends of the spectrum of working with the historical and thinking about the ways things would be found or left in in the future.

So that’s definitely what pushes me to find more works by women and finding ways of theorizing and of the archive and new methodologies that don’t just rely on physical documentation, which might be nonexistent or limited, right? In teaching and writing about women writers there’s this question of, you know, there’s no parity in the amount of documents that are available about men versus the amount of documents there about women.

In teaching and writing about women writers […] there’s no parity in the amount of documents that are available about men versus the amount of documents there about women. And while that may never be equal […] there’s other ways we can think about the oral traditions, the memories, other things that have been left behind…

And while that may never be equal, because they might not all be found or available, there’s other ways we can think about the oral traditions, the memories, other things that have been left behind, as a way of bridging the past and what we will bring into the future. Because, you know, there’s a lot of talk today about plastic and things that have been left in the Earth, and these kind of thought experiment articles that pop up on Google about, you know, what will our legacy be in terms of physical artefacts a hundred years from now, or something like that.

BH: Yeah, I’m thinking about “Life Capsule,” which we did mention a little bit earlier, but, yeah, like you said, we didn’t really go into it in any depth. The speaker in that poem, which is right towards the beginning of the collection, as they’re putting together this life capsule and including things like a book with paper made from a forest that no longer exist[s], and rings with apartheid diamonds, and other indications of how life was in the time that the speaker is coming from, which seems to be in a near future to us—

AA: Mhm.

BH: —that speaker does mention that whoever opens this capsule will probably write an article or listicle making socially inaccurate suppositions, yeah. So you’re touching on those themes. And they say, “I’m sincerely sorry for your assumptions,” and I’m sure when you wrote this you had in mind a number of present-day pieces of academic, or, you know, popular kind of academic writing that comes up on Google and other places that push algorithm-fed suggestions at us.

Yeah, it is an interesting thought that even in the case of a life capsule—it’s somebody who is including things with the intention of having someone in the future find them in order to be able to learn about the past—even in this specific case, where they are leaving very intentional indications as to how we lived, they assume whoever finds this is going to get it wrong, regardless. You can’t actually give someone a fully accurate picture of what life is like now, when we’re talking about a past that’s buried in centuries of divergent experience.

I do believe that you mention plastics in here, and I was trying to remember, you had a line about “the plastics that we exude from our pores,” or something along those lines somewhere in here. I couldn’t find it. But that is an element of our life today that’s very different from what we’ve seen in past generations. I wonder if we’re going to be known as the Plastic Age, or… time will tell, but we won’t be around to see it. But, yeah, it is an interesting thing to speculate on.

In another poem in your collection, “Leaving Footprints,” you talk about how we leave these marks of our existence, but we can’t really expect them to last, to be interpreted fully and understood fully by the people who come afterwards. But despite that, you know, there is something we are leaving behind, some sign of our interactions with the Earth now.

AA: I also think that having written it first in Spanish, with the title being “Dejando huellas,” leaving footprints kind of carries that secondary meaning of, like, leaving other things behind, leaving your legacy, leaving trails of yourself, right?

BH: Yeah, that poem was presented first in Spanish and then in English, and not all of the poems in this collection are. A lot of them are presented only in English.

But there’s a few that are in Spanish and then in English and, yes, “Dejando huellas” is—first we see it in Spanish, and then we see it [as] “Leaving Footprints” in English, which is a more specific reading than… huellas is a bit broader, like it could be a number of different kinds of marks, yes.

So, I was wondering about, in general, with the poetry that you publish in Spanish and in English as parallel, or sort of side-by-side, texts, does it normally come out first for you in Spanish and then in English, or the other way around? Or are there pieces that you write at the same time, simultaneously, and then sort of pull apart into two separate language texts? Or how does this usually go for you?

AA: Yeah, I should clarify that I’m not a native Spanish speaker. My family doesn’t speak Spanish, so I learned it in school and became fluent through school and other sorts of kind of extracurricular activities that gave me more exposure to the language. And writing in Spanish then begs the question of what publication venues are available, because being a US-based writer, there are a lot of venues for Latinx writers that do accept Spanish work, but in general it’s, you know… the publication landscape, especially for speculative work, is English. So I focus my poetic output and writing in English.

And, again, because I’m not a native speaker, I don’t think I necessarily want to write as many poems in Spanish as I do in English.

When it does come to writing in Spanish, I’m very intentional about the intentionality behind it and the poetic voices that appear in the poem, of recognizing that this is a poem written by and for Spanish speakers with this particular history attached to it, with the Latinx diaspora, with the ways the Spanish language has been used and forgotten over the years.

So, typically I’ll write the poem in Spanish, and it may be that I’ll, you know, write parts of it and then translate the parts that I’ve already written, but I don’t necessarily go back and forth, other than through the translation itself, and I always feel a bit strange seeing these poems come into English translation, but I do realize it’s a necessity when it comes to a publication landscape where you probably need to provide a translation.

I’d love to do more translation work of other writers’ work in the future, and getting the publication rights to do so for the poets and writers that I study would be really great.

So, yeah, so I do tend to write a poem first in Spanish and then, either in the process of or after having written the poem, it will go into English. But I try not to let the English language, or the way it looks in English, inform the Spanish composition of the poem.

I try not to let the English language, or the way it looks in English, inform the Spanish composition of the poem.

BH: The poems that you write in Spanish, you have very much a Spanish-speaking audience in mind, because of the specific topics you’re tackling.

Yeah, I can see that definitely in “Dejando huellas,” “Leaving Footprints,” which touches on specifically Florida, and then Spain, and the historical connection between those, and the speaker’s experience of those sort of cultural and historical ties. Definitely something that makes sense as a topic that would be of interest to Spanish speakers.

But I was wondering because—even though it’s a language that you learned later on, Spanish—you’ve done a lot of reading in Spanish, that’s been your scholarly focus for quite a while now, when you are writing creatively, whether in Spanish or in English, do you find—not only in theme, because we’ve talked a lot about theme and sort of ideas that are being tackled in your writing—but in the way you word things, in the structures you employ, that sort of side of writing, do you find yourself influenced when you write in English by any of the Spanish reading you do? Or the other way around? Is there any sort of overlap in influences going one way or the other?

AA: I think I’m much more linguistically influenced in Spanish by what I’ve been reading in Spanish.

I think it’s simply being a non-native speaker, you know, you might be gravitated towards certain phrases or certain expressions, or you hear something…

I mean, I spent a lot of time translating the work of Vicente Aleixandre, who lived during the 20th century and was a Nobel Laureate in Literature from Spain. So a lot of what he writes is kind of, you know, floating around my mind when I think of poetry in Spanish.

I think I pay more attention to—because, again, the language is different, it’s a gender-based language—to rhyme, to the ways things flow. Because there’s more verb tenses than in English, I like to kind of match things a little more intentionally, or have more coherence. And just making sure that, you know, the grammar is as it should be, and there’s that sort of connection between each stanza there.

BH: Yeah. I haven’t read work by Vicente Aleixandre, but reading your writing in Spanish—which we’re going to get to hear a little bit of a little later on in the episode, because you have a poem to read us that you wrote in Spanish and then in English translation of your own—it does seem like you have sort of a very precise and almost, like, analytical way of writing, and I wonder if I read work by Vicente Aleixandre, if I’ll start to pick up on where you’re coming from with that.

AA: I don’t think that itself is from Aleixandre. I think it’s moreso the way I handle the language is just going to be different than somebody who might have grown up speaking it in that different relationship they may have, just having spoken it and using more informal words versus me learning it for a more academic context, and then that coming out in my writing, especially since, like, writing essays in prose in Spanish is quite different.

There’s the structure behind it, the language used, you know, the fact that Spanish sentences can be much longer than English sentences, and they put the prepositions in the middle, those sorts of things, versus somebody who might write Spanish as a native speaker and be able to kind of use shorter phrases, or just handle it a little bit differently.

So I think that’s more just on me and my own abilities and background with the language, and then seeing what I like of other writers.

BH: Hm. You’re drawing more exclusively from written sources, as opposed to from written and verbal?

AA: Sure. Especially when it comes to writing poetry, just because I haven’t regularly been writing poetry in Spanish the same way I’ve been regularly writing more academic, or just even emails, you know, other sorts of writing and speaking in Spanish.

BH: Ok. Yeah, well, [a formal, analytical style is] not something to be necessarily avoided in poetry. It’s, you know, a matter of choice, whether someone’s a native speaker or writing in something that’s their second language, which I’m sure you run into in plenty of cases with the writers in Spain who are writing in Spanish, since some of them probably come from Galician-, or Catalan-, or other language-speaking backgrounds as well, and chose Spanish as sort of the language of prestige, or as what was possible to write in at the time. So even within the literature of Spain, there’s plenty of people writing in Spanish as a second language.

But, yeah, it’s interesting in the collection in English, as well—it’s not restricted to Spanish—but you have, as I mentioned, a lot of different opinions expressed by these different speakers, but also different sorts of voices in the sense of the kinds of structures, the kinds of sentence structures, even, that we see employed in the English poems as well. So, I do think it covers a lot of different stylistic ground.

However, you mentioned rhyme right now, and I was thinking… rhyme, it didn’t come up. In this collection, anyway, I believe all your poems are free verse, right?

AA: Yes.

BH: Hm. Do you do rhyming poetry as well?

AA: I wouldn’t say I do. I think for me, I’m a much more visual person than someone who’s going to handle the sonic qualities of a poem, so that’s what I personally focus on in terms of creating. And I think with the avant-garde writing that I study, they’re really focused on metaphor and the surrealist vision.

So even though my work is very different in context, scope, and the linguistic register of the poem, there’s still that primary need to focus on the visual over the listening, the sound quality.

So that’s kind of just a preference for me, as a poet, in how I handle my own free verse writing. And I think lately I’ve been playing more with writing prose poems, shorter poetry, and just kind of branching out of the kind of structures that I’ve kind of leaned on heavily in free verse writing, meaning that I oftentimes will write a poem with about six stanzas, 4-6 lines a stanza, and creating a story that way in the poetry, and then nowadays deciding to write more things as prose poems, or short poems, or things that don’t follow that structure. And I like being able to start with an idea and decide whether it’s going to be a flash fiction piece or whether it’s going to be poetry

But yeah, I’m not a big rhyming poet. I also don’t write short form poems like haikus or things like that at the moment.

BH: Hm. So you’re saying you usually—it’s between flash fiction and poetry for you right now. How do you make that decision? Like, lately, what have you found to be the determining factor between poem or flash fiction piece?

AA: That’s a good question. I think if I wanted to develop the characters and have a particular story arc in mind, it’s probably going to move towards flash fiction. If I already kind of have some bullet points or an outline in mind, sometimes it’s very short and I just decide to do a prose poem or something.

It also depends on what publication venue I’m targeting, since I write far less fiction than I do poetry. I’ve been trying to build more of a portfolio of writing fiction when I’m able to.

BH: Yeah, it’s super interesting to me that you mentioned a couple times already that two or three years ago, you weren’t even all that aware that there was such a thing as sci-fi and fantasy poetry as a genre that people were dedicated to writing in, and you almost immediately—if that’s the time frame we’re talking about—put together an entire collection of sci-fi poetry. And that was one of your first fiction publications!

I mean, because you have other scholarly essays, and articles, and things that you have out there already as part of your academic work, but one of the first things you have published is a book full of sci-fi poetry. That sounds like a very fast turnaround from somebody who didn’t know it was out there to almost dedicating—you said you write a lot more poetry rather than prose fiction for the moment when you’re looking into speculative genres?

AA: Mhm. Yeah, so I guess, to backtrack a little bit, I’ve been writing poetry since basically the beginning of high school, but it was very much contemporary literary work. And I never really felt that it was well received or understood, and not just like in a teenage angst kind of way, but just not quite finding my footing with the particular contemporary poetry concerns, the world around that writing.

And I didn’t necessarily want to write about myself, and I think once I started going in the direction of writing speculative work, I just knew immediately that’s where I wanted my writing to be focused on. So, even though it was new to me I also really gravitated towards it in a way that the contemporary poetry didn’t stick.

…once I started going in the direction of writing speculative work, I just knew immediately that’s where I wanted my writing to be focused on.

So, I do, you know, write contemporary poetry, and my chapbook Fourth Generation Chicana Unicorn is in a more contemporary type of genre than it is speculative. But at the same time, it’s growing out of my engagement with what’s possible through speculative poetry, what’s possible if one goes in one’s own direction and [is] not just trying to write for what you think that people want to read.

So, yeah, I basically that first year started writing a whole lot of science fiction poetry, speculative poetry—I don’t really write fantasy poetry or horror—and in publishing those, then started putting together this collection, and then have continued to publish since then.

The fiction then kind of came later. I was, again, figuring out where I wanted to go with fiction. I was writing a dissertation at the time, I didn’t want to write too long of fiction. I wanted to make sure that I was allocating enough time and space for writing academic work. But I really enjoyed writing a flash pieces in particular, and just want to continue writing that now that I feel a little bit more confident in character development, world building.

But I definitely am more—I like poetry more, because I’m not as interested in writing dialogue. I know that’s a big part of writing fiction, and that isn’t always what I want to be spending the most time writing.

BH: The “unicorn” in Fourth Generation Chicana Unicorn is purely metaphorical, then, I take it? I haven’t read that one.

AA: Oh, yes. [Laughter.]

BH: Ok. Since you were saying you don’t really write much fantasy.

AA: Yeah.

BH: All right. You said that that chapbook is a little bit of a mix? So there is some speculative elements we should be looking out for if we pick up Fourth Generation Chicana Unicorn, or…?

AA: Uh, not quite. I think it’s just kind of how I’ve grown as a poet, as a speculative writer, kind of went into putting that collection together. And that collection represents a larger time frame of my work, from I think about six years or so of my work. And questions about identity, belonging, and having gained the label of being a “Chicana unicorn” and then adding “fourth generation” to that on my own.

BH: So it’s a sci-fi writing-influenced, non-sci-fi chapbook, pretty much.

AA: Yeah, I suppose. It’s definitely contemporary, but not necessarily the types of linguistic registers, types of topics that are often picked up in what folks are publishing in contemporary venues.

BH: Ok, yeah. Having discussed, you know, the poetry that you’re writing—mainly in English, but also in Spanish—and more specifically a lot of the sci-fi stuff you’ve been working on, you did select a poem that kind of went in line with this discussion to read for us today. And it first appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of Star*Line, so it’s a relatively recent poem.

It was published in Spanish and in English, both versions by you, in Star*Line 46.1, and I understand you’re going to read us the Spanish and the English for this podcast episode?

AA: Yes.

BH: Yes, so whenever you’re ready, we’d love to hear both versions, the Spanish and English.

AA: Yeah, so this comes from the Xenopoetry endsection of Star*Line. They always include a piece originally written in a language other than English and, as is sometimes the case, the writer of the original piece also translates their work, but not always.

So I’ll be first reading the poem “Prayer for the Old Voyagers of Earth” in Spanish. And the title of that is “Oración para los antiguos viajeros de la Tierra.” So I’ll go ahead and read it in Spanish, and then read you the English translation that I also composed.

Oración para los antiguos viajeros de la Tierra

Lo hacemos por ti, el merecido colofón

del progreso humano desde el hidrógeno de las estrellas

hasta el hierro de los cohetes.

Te amamos con la furia de un alma familiar,

alabando a la sombra amplia de tus descubrimientos

y el abanico de nuevos mundos que nos has brindado.

Celebramos las culturas que has guardado en tu seno,

las lenguas secretas que han calculado distancias inmensas del ultramar.

Reconocemos tus desastres y los nuestros, y el orgullo que siempre

nos echa pa’lante. Te agradecemos hasta que desaparezcan las últimas palabras.

Prayer for the Old Voyagers of Earth

We do this for you, the well-deserved culmination

of human progress from the hydrogen of the stars

to the iron of our rockets.

We love you with the fervor of close family,

praising the broad shadow of your discoveries

and the spectrum of new worlds that you have provided us.

We celebrate the cultures that you have safeguarded under your wing,

the secret languages that have calculated immense oversea distances.

We recognize your disasters and our own, and the pride that keeps

us moving forward, pa’lante. We thank you until the last words disappear.

BH: Yeah. Thank you.

I really enjoyed this poem because it has the cadence, or it [gives] the impression, of being a set prayer. I mean, it’s called “Prayer for the Old Voyagers of Earth,” as you just told us, but it gives the impression of being a sort of a ritual prayer.

It reads as something that’s memorized, that’s passed down. So this is a future where not only has humanity long ago left the confines of Earth, but they’ve built up traditions surrounding this almost mythical exodus that they’ve made from the planet—

AA: Mhm!

BH: —and they have customs in place, ways of discussing it that are passed down through the generations, and so it really very neatly puts us into this future setting, and kind of integrates us as listeners into this future setting, in a way that I think is really interesting.

And in the overall poem, it’s pretty formal, both in Spanish and English—so this isn’t only a reflex of your writing in Spanish, I believe. It’s in the English version as well, it was a choice you made there.

AA: Mhm.

BH: Which contributes to it being read as a sort of ritual prayer, something that people are memorizing, passing on.

However, in the last line, we’ve got a little bit of eye dialect with pa’lante. I mean, there’s an apostrophe there to tell us, you know, you’re not supposed to read “para”—which would be the sort of formal written way of saying para adelante—we’re supposed to say “pa’lante”—and this is a very overtly informal or casual element of speech.

I was wondering what made you choose to throw in at the last line this casual element of, like, colloquial Spanish, which you have integrated into the English version as well? You didn’t translate that, you just meshed it in with the English. So what was it about pa’lante that made you want to throw in that casual bit of wording at the very end?

AA: I think pa’lante is just a very—when you think of the future, and thinking of moving forward, it’s so often said in Spanish, especially when kind of imagining what’s possible, pa’lante, moving forward, that I didn’t even consider writing para adelante. Because I wanted that sense of “we are moving forward,” and that’s kind of that connection back to the people, not just being this written document, but people moving forward and understanding it as such, as just moving forward.

So it wasn’t so much I wanted to mix the colloquial with the formal, but moreso just the initial feeling of this is how this would be said.

BH: Hm. I thought it was a really kind of cool choice, because when I was reading it before hearing you read it out loud, just on the page, you know, I was experiencing this first as a written text, first and foremost, and there was nothing to kind of make me recast it as an orally transmitted text until we get to the end, and suddenly this pa’lante leaps out at you as a very overtly verbal element. And it sort of reframed the entire piece for me as something that is being spoken.

AA: Mhm.